Introduction

Immunizations have saved at least 154 million lives in the last 50 years and are one of the most important tools in preventive health care. They are a large contributor to the worldwide increases in life expectancy in the past century.

Vaccines work in different ways, often by introducing an antigen in the form of a weakened or inactivated version of a pathogen. This teaches immune cells to recognize the germ, so they are ready if they encounter it. mRNA vaccines, such as the COVID-19 vaccines, work by teaching our cells to make a protein which immune cells then respond to.

National Immunization Awareness Month

August is National Immunization Awareness Month, during which the importance of immunizations is highlighted, and people of all ages are encouraged to get their routine vaccinations. The observance was originally developed by the National Public Health Information Coalition and is now championed by CDC.

Vaccines and Health Equity

Equitable access to vaccines is a key issue in the U.S. and around the world. CDC partners with organizations working on health equity to improve immunization access. Together with these partners, they aim to share resources, provide peer learning, connect subject matter experts, and create platforms for collaboration. The National Vaccine Advisory Committee notes that including marginalized populations in immunization programs also connects them with health care, generating a healthier nation overall.

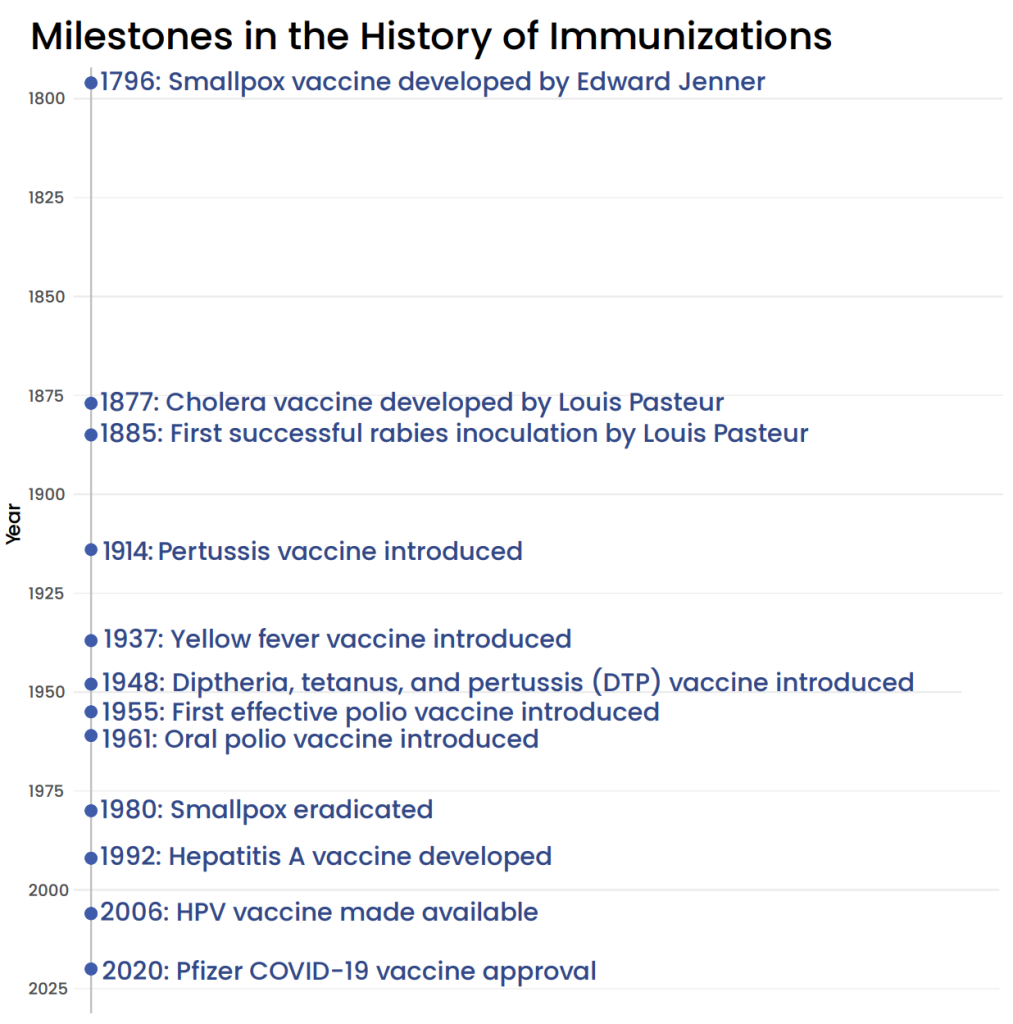

History of Immunizations

The earliest documented event in the history of vaccines was in the 15th century, when people around the world aimed to prevent smallpox by exposing healthy people to the virus. In a 1774 breakthrough, Benjamin Jesty tested whether infection with cowpox could protect against smallpox. In 1796, Edward Jenner began by inoculating a young patient with material from a cowpox sore, then tested the patient’s resistance to smallpox. The word “vaccine” is derived from “vacca,” the Latin word for cow.

The earliest documented event in the history of vaccines was in the 15th century, when people around the world aimed to prevent smallpox by exposing healthy people to the virus. In a 1774 breakthrough, Benjamin Jesty tested whether infection with cowpox could protect against smallpox. In 1796, Edward Jenner began by inoculating a young patient with material from a cowpox sore, then tested the patient’s resistance to smallpox. The word “vaccine” is derived from “vacca,” the Latin word for cow.

Immunization development for influenza began during the 1918 influenza pandemic, though the U.S. Army Medical School’s results remained ambiguous at the time. In 1946 the first influenza vaccines were made available for civilians.

In the 1950s, Jonas Salk tested the first effective polio vaccine on himself and his family, and trials among children began. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative began in 1988. As of 2024, 2 of 3 wild poliovirus strains have been eliminated, with polio only endemic in two remaining countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The pilot program for the first malaria vaccine began in 2019. A vaccine has been developed for Ebolavirus and a stockpile has been established to prepare the world for future outbreaks. An updated smallpox vaccine, JYNNEOS, is used for preventing mpox and was key to controlling the spread of the virus in 2022.

Researchers began developing mRNA vaccines in the 1970s, and these vaccines were rolled out as the first COVID-19 vaccines in 2021.

COVID-19 Vaccines in the U.S. and Around the World

The COVID-19 vaccines are estimated to have saved millions of lives. In the U.S. in the first 6 months of vaccine availability, an estimated hundreds of thousands of deaths were averted. As with other health interventions, health equity for COVID-19 vaccines is an important aspect of distribution and access.

With commercialization of COVID-19 vaccines in August and September 2023, Lefkowitz and coauthors wondered whether commercialization would affect COVID-19 vaccine equity, as payment transitioned from government procurement to Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance payment mechanisms. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response aimed to keep COVID-19 vaccine accessible through private insurance, and for people without insurance in the U.S. through CDC’s Vaccines for Children Program, Federally Qualified Health Centers, Rural Health Clinics, and local health departments.

Throughout the pandemic, state and international programs, sought to provide equal access to COVID-19 vaccines. In California, prioritized vaccine access using the Healthy Places Index, and increased vaccination rates in disadvantaged communities by 28.4%. While these efforts did not completely mitigate disparities in COVID-19 cases and hospitalization rates, they prevented hundreds of deaths.

Address Misinformation and Disinformation About Vaccines

According to CDC, “misinformation is false information shared by people who do not intend to mislead others,” while “disinformation is false information deliberately created and disseminated with malicious intent.” Both can contribute to vaccine hesitancy.

Misinformation about vaccines can be addressed with clear messages about what we know and being open about uncertainties which remain in the science. CDC recommends analyzing misinformation which is shared on social media in your community, which can help identify gaps in information and content which are relevant to the community. Then, share accurate information which fills the gaps across a wide range of media, from social media to signs in public places and radio. This will help reach people who are not online. Public health organizations can partner with trusted messengers, like community or religious leaders, to promote the benefits of vaccines and address questions from community members.

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research identifies additional strategies for addressing misinformation. They recommend highlighting the scientific consensus, using humor to address incorrect information about vaccines, and including misinformation warnings on search platforms and social media.

Rebuild Trust

Address historical injustices and current experiences of discrimination that may contribute to vaccine hesitancy. Communities may be skeptical of the health care system due to historical injustices and current experiences of discrimination. Rebuilding trust can involve acknowledging past wrongs, implementing policies to prevent future injustices, and working to improve the overall patient experience. Rebuilding trust is important to ensuring communities feel confident in vaccination programs. CDC’s guide for community partners provides strategies for including people from racial and ethnic minority communities in vaccination campaigns for COVID-19, since minority communities are disproportionately affected by it. Among CDC’s recommendations to facilitate communications and confidence in and access to vaccines, the guide encourages coordination with state and local health departments and supporting members of the community to share the benefits of vaccines. Culturally relevant information in the languages spoken by the community, transparency about cost, online and text message campaigns, and providing information by TV or radio are important tools for rebuilding trust.

Conclusion

Vaccines are lifesaving innovations that have contributed to the considerable gains in life expectancy the world has seen in the past century since their discovery. Health equity in vaccine access in the U.S. and around the world remains an important challenge, especially as misinformation about immunizations persists. Clear, accurate information from trusted sources is important to mitigate the impacts of misinformation. By communicating clearly about vaccines and encouraging routine immunizations, we can save lives.

Interested in learning more?

For more on immunizations, check out P4HE’s partner organization, the National Medical Association (NMA). Their page on NMA President Oliver T. Brooks’ biography provides insight on an NMA leader who supported immunization programs in California.